Overview

On this publish, we’ll evaluation three superior strategies for enhancing the efficiency and generalization energy of recurrent neural networks. By the top of the part, you’ll know most of what there may be to learn about utilizing recurrent networks with Keras. We’ll display all three ideas on a temperature-forecasting downside, the place you might have entry to a time collection of information factors coming from sensors put in on the roof of a constructing, comparable to temperature, air strain, and humidity, which you utilize to foretell what the temperature will probably be 24 hours after the final information level. This can be a pretty difficult downside that exemplifies many widespread difficulties encountered when working with time collection.

We’ll cowl the next strategies:

- Recurrent dropout — This can be a particular, built-in approach to make use of dropout to battle overfitting in recurrent layers.

- Stacking recurrent layers — This will increase the representational energy of the community (at the price of greater computational hundreds).

- Bidirectional recurrent layers — These current the identical data to a recurrent community in several methods, rising accuracy and mitigating forgetting points.

A temperature-forecasting downside

Till now, the one sequence information we’ve lined has been textual content information, such because the IMDB dataset and the Reuters dataset. However sequence information is discovered in lots of extra issues than simply language processing. In all of the examples on this part, you’ll play with a climate timeseries dataset recorded on the Climate Station on the Max Planck Institute for Biogeochemistry in Jena, Germany.

On this dataset, 14 totally different portions (such air temperature, atmospheric strain, humidity, wind route, and so forth) have been recorded each 10 minutes, over a number of years. The unique information goes again to 2003, however this instance is restricted to information from 2009–2016. This dataset is ideal for studying to work with numerical time collection. You’ll use it to construct a mannequin that takes as enter some information from the current previous (a couple of days’ value of information factors) and predicts the air temperature 24 hours sooner or later.

Obtain and uncompress the info as follows:

dir.create("~/Downloads/jena_climate", recursive = TRUE)

obtain.file(

"https://s3.amazonaws.com/keras-datasets/jena_climate_2009_2016.csv.zip",

"~/Downloads/jena_climate/jena_climate_2009_2016.csv.zip"

)

unzip(

"~/Downloads/jena_climate/jena_climate_2009_2016.csv.zip",

exdir = "~/Downloads/jena_climate"

)Let’s take a look at the info.

Observations: 420,551

Variables: 15

$ `Date Time` <chr> "01.01.2009 00:10:00", "01.01.2009 00:20:00", "...

$ `p (mbar)` <dbl> 996.52, 996.57, 996.53, 996.51, 996.51, 996.50,...

$ `T (degC)` <dbl> -8.02, -8.41, -8.51, -8.31, -8.27, -8.05, -7.62...

$ `Tpot (Okay)` <dbl> 265.40, 265.01, 264.91, 265.12, 265.15, 265.38,...

$ `Tdew (degC)` <dbl> -8.90, -9.28, -9.31, -9.07, -9.04, -8.78, -8.30...

$ `rh (%)` <dbl> 93.3, 93.4, 93.9, 94.2, 94.1, 94.4, 94.8, 94.4,...

$ `VPmax (mbar)` <dbl> 3.33, 3.23, 3.21, 3.26, 3.27, 3.33, 3.44, 3.44,...

$ `VPact (mbar)` <dbl> 3.11, 3.02, 3.01, 3.07, 3.08, 3.14, 3.26, 3.25,...

$ `VPdef (mbar)` <dbl> 0.22, 0.21, 0.20, 0.19, 0.19, 0.19, 0.18, 0.19,...

$ `sh (g/kg)` <dbl> 1.94, 1.89, 1.88, 1.92, 1.92, 1.96, 2.04, 2.03,...

$ `H2OC (mmol/mol)` <dbl> 3.12, 3.03, 3.02, 3.08, 3.09, 3.15, 3.27, 3.26,...

$ `rho (g/m**3)` <dbl> 1307.75, 1309.80, 1310.24, 1309.19, 1309.00, 13...

$ `wv (m/s)` <dbl> 1.03, 0.72, 0.19, 0.34, 0.32, 0.21, 0.18, 0.19,...

$ `max. wv (m/s)` <dbl> 1.75, 1.50, 0.63, 0.50, 0.63, 0.63, 0.63, 0.50,...

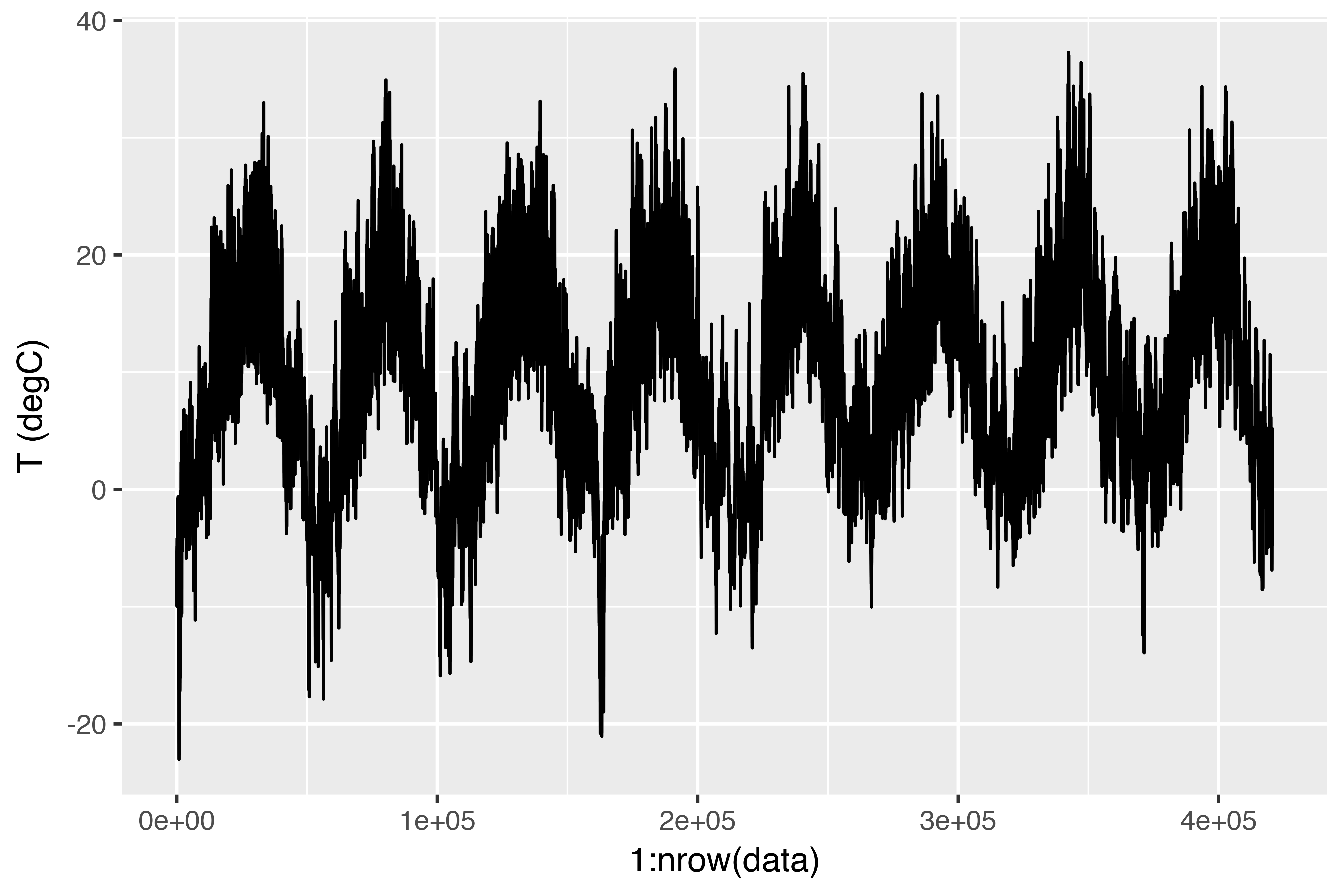

$ `wd (deg)` <dbl> 152.3, 136.1, 171.6, 198.0, 214.3, 192.7, 166.5...Right here is the plot of temperature (in levels Celsius) over time. On this plot, you possibly can clearly see the yearly periodicity of temperature.

Here’s a extra slender plot of the primary 10 days of temperature information (see determine 6.15). As a result of the info is recorded each 10 minutes, you get 144 information factors

per day.

ggplot(information[1:1440,], aes(x = 1:1440, y = `T (degC)`)) + geom_line()

On this plot, you possibly can see every day periodicity, particularly evident for the final 4 days. Additionally word that this 10-day interval should be coming from a reasonably chilly winter month.

When you have been making an attempt to foretell common temperature for the following month given a couple of months of previous information, the issue could be simple, because of the dependable year-scale periodicity of the info. However trying on the information over a scale of days, the temperature seems to be much more chaotic. Is that this time collection predictable at a every day scale? Let’s discover out.

Making ready the info

The precise formulation of the issue will probably be as follows: given information going way back to lookback timesteps (a timestep is 10 minutes) and sampled each steps timesteps, can you expect the temperature in delay timesteps? You’ll use the next parameter values:

lookback = 1440— Observations will return 10 days.steps = 6— Observations will probably be sampled at one information level per hour.delay = 144— Targets will probably be 24 hours sooner or later.

To get began, that you must do two issues:

- Preprocess the info to a format a neural community can ingest. That is simple: the info is already numerical, so that you don’t must do any vectorization. However every time collection within the information is on a distinct scale (for instance, temperature is often between -20 and +30, however atmospheric strain, measured in mbar, is round 1,000). You’ll normalize every time collection independently in order that all of them take small values on an analogous scale.

- Write a generator perform that takes the present array of float information and yields batches of information from the current previous, together with a goal temperature sooner or later. As a result of the samples within the dataset are extremely redundant (pattern N and pattern N + 1 could have most of their timesteps in widespread), it might be wasteful to explicitly allocate each pattern. As a substitute, you’ll generate the samples on the fly utilizing the unique information.

NOTE: Understanding generator features

A generator perform is a particular kind of perform that you simply name repeatedly to acquire a sequence of values from. Usually turbines want to take care of inner state, so they’re sometimes constructed by calling one other one more perform which returns the generator perform (the atmosphere of the perform which returns the generator is then used to trace state).

For instance, the sequence_generator() perform under returns a generator perform that yields an infinite sequence of numbers:

sequence_generator <- perform(begin) {

worth <- begin - 1

perform() {

worth <<- worth + 1

worth

}

}

gen <- sequence_generator(10)

gen()[1] 10[1] 11The present state of the generator is the worth variable that’s outlined outdoors of the perform. Observe that superassignment (<<-) is used to replace this state from inside the perform.

Generator features can sign completion by returning the worth NULL. Nevertheless, generator features handed to Keras coaching strategies (e.g. fit_generator()) ought to all the time return values infinitely (the variety of calls to the generator perform is managed by the epochs and steps_per_epoch parameters).

First, you’ll convert the R information body which we learn earlier right into a matrix of floating level values (we’ll discard the primary column which included a textual content timestamp):

You’ll then preprocess the info by subtracting the imply of every time collection and dividing by the usual deviation. You’re going to make use of the primary 200,000 timesteps as coaching information, so compute the imply and normal deviation for normalization solely on this fraction of the info.

The code for the info generator you’ll use is under. It yields a listing (samples, targets), the place samples is one batch of enter information and targets is the corresponding array of goal temperatures. It takes the next arguments:

information— The unique array of floating-point information, which you normalized in itemizing 6.32.lookback— What number of timesteps again the enter information ought to go.delay— What number of timesteps sooner or later the goal ought to be.min_indexandmax_index— Indices within theinformationarray that delimit which timesteps to attract from. That is helpful for maintaining a phase of the info for validation and one other for testing.shuffle— Whether or not to shuffle the samples or draw them in chronological order.batch_size— The variety of samples per batch.step— The interval, in timesteps, at which you pattern information. You’ll set it 6 as a way to draw one information level each hour.

generator <- perform(information, lookback, delay, min_index, max_index,

shuffle = FALSE, batch_size = 128, step = 6) {

if (is.null(max_index))

max_index <- nrow(information) - delay - 1

i <- min_index + lookback

perform() {

if (shuffle) {

rows <- pattern(c((min_index+lookback):max_index), dimension = batch_size)

} else {

if (i + batch_size >= max_index)

i <<- min_index + lookback

rows <- c(i:min(i+batch_size-1, max_index))

i <<- i + size(rows)

}

samples <- array(0, dim = c(size(rows),

lookback / step,

dim(information)[[-1]]))

targets <- array(0, dim = c(size(rows)))

for (j in 1:size(rows)) {

indices <- seq(rows[[j]] - lookback, rows[[j]]-1,

size.out = dim(samples)[[2]])

samples[j,,] <- information[indices,]

targets[[j]] <- information[rows[[j]] + delay,2]

}

checklist(samples, targets)

}

}The i variable comprises the state that tracks subsequent window of information to return, so it’s up to date utilizing superassignment (e.g. i <<- i + size(rows)).

Now, let’s use the summary generator perform to instantiate three turbines: one for coaching, one for validation, and one for testing. Every will take a look at totally different temporal segments of the unique information: the coaching generator seems to be on the first 200,000 timesteps, the validation generator seems to be on the following 100,000, and the take a look at generator seems to be on the the rest.

lookback <- 1440

step <- 6

delay <- 144

batch_size <- 128

train_gen <- generator(

information,

lookback = lookback,

delay = delay,

min_index = 1,

max_index = 200000,

shuffle = TRUE,

step = step,

batch_size = batch_size

)

val_gen = generator(

information,

lookback = lookback,

delay = delay,

min_index = 200001,

max_index = 300000,

step = step,

batch_size = batch_size

)

test_gen <- generator(

information,

lookback = lookback,

delay = delay,

min_index = 300001,

max_index = NULL,

step = step,

batch_size = batch_size

)

# What number of steps to attract from val_gen as a way to see the complete validation set

val_steps <- (300000 - 200001 - lookback) / batch_size

# What number of steps to attract from test_gen as a way to see the complete take a look at set

test_steps <- (nrow(information) - 300001 - lookback) / batch_sizeA typical-sense, non-machine-learning baseline

Earlier than you begin utilizing black-box deep-learning fashions to resolve the temperature-prediction downside, let’s attempt a easy, commonsense method. It should function a sanity verify, and it’ll set up a baseline that you simply’ll must beat as a way to display the usefulness of more-advanced machine-learning fashions. Such commonsense baselines will be helpful if you’re approaching a brand new downside for which there is no such thing as a recognized answer (but). A basic instance is that of unbalanced classification duties, the place some courses are way more widespread than others. In case your dataset comprises 90% cases of sophistication A and 10% cases of sophistication B, then a commonsense method to the classification job is to all the time predict “A” when introduced with a brand new pattern. Such a classifier is 90% correct total, and any learning-based method ought to due to this fact beat this 90% rating as a way to display usefulness. Typically, such elementary baselines can show surprisingly arduous to beat.

On this case, the temperature time collection can safely be assumed to be steady (the temperatures tomorrow are prone to be near the temperatures at present) in addition to periodical with a every day interval. Thus a commonsense method is to all the time predict that the temperature 24 hours from now will probably be equal to the temperature proper now. Let’s consider this method, utilizing the imply absolute error (MAE) metric:

Right here’s the analysis loop.

This yields an MAE of 0.29. As a result of the temperature information has been normalized to be centered on 0 and have a typical deviation of 1, this quantity isn’t instantly interpretable. It interprets to a mean absolute error of 0.29 x temperature_std levels Celsius: 2.57˚C.

celsius_mae <- 0.29 * std[[2]]That’s a pretty big common absolute error. Now the sport is to make use of your information of deep studying to do higher.

A fundamental machine-learning method

In the identical approach that it’s helpful to determine a commonsense baseline earlier than making an attempt machine-learning approaches, it’s helpful to attempt easy, low cost machine-learning fashions (comparable to small, densely linked networks) earlier than trying into sophisticated and computationally costly fashions comparable to RNNs. That is the easiest way to verify any additional complexity you throw on the downside is reliable and delivers actual advantages.

The next itemizing exhibits a completely linked mannequin that begins by flattening the info after which runs it by way of two dense layers. Observe the dearth of activation perform on the final dense layer, which is typical for a regression downside. You utilize MAE because the loss. Since you consider on the very same information and with the very same metric you probably did with the common sense method, the outcomes will probably be straight comparable.

library(keras)

mannequin <- keras_model_sequential() %>%

layer_flatten(input_shape = c(lookback / step, dim(information)[-1])) %>%

layer_dense(models = 32, activation = "relu") %>%

layer_dense(models = 1)

mannequin %>% compile(

optimizer = optimizer_rmsprop(),

loss = "mae"

)

historical past <- mannequin %>% fit_generator(

train_gen,

steps_per_epoch = 500,

epochs = 20,

validation_data = val_gen,

validation_steps = val_steps

)Let’s show the loss curves for validation and coaching.

A number of the validation losses are near the no-learning baseline, however not reliably. This goes to point out the advantage of getting this baseline within the first place: it seems to be not simple to outperform. Your widespread sense comprises a variety of precious data {that a} machine-learning mannequin doesn’t have entry to.

Chances are you’ll marvel, if a easy, well-performing mannequin exists to go from the info to the targets (the common sense baseline), why doesn’t the mannequin you’re coaching discover it and enhance on it? As a result of this easy answer isn’t what your coaching setup is on the lookout for. The area of fashions wherein you’re trying to find an answer – that’s, your speculation area – is the area of all potential two-layer networks with the configuration you outlined. These networks are already pretty sophisticated. While you’re on the lookout for an answer with an area of sophisticated fashions, the easy, well-performing baseline could also be unlearnable, even when it’s technically a part of the speculation area. That could be a fairly important limitation of machine studying on the whole: except the training algorithm is hardcoded to search for a selected type of easy mannequin, parameter studying can typically fail to discover a easy answer to a easy downside.

A primary recurrent baseline

The primary totally linked method didn’t do properly, however that doesn’t imply machine studying isn’t relevant to this downside. The earlier method first flattened the time collection, which eliminated the notion of time from the enter information. Let’s as an alternative take a look at the info as what it’s: a sequence, the place causality and order matter. You’ll attempt a recurrent-sequence processing mannequin – it ought to be the right match for such sequence information, exactly as a result of it exploits the temporal ordering of information factors, not like the primary method.

As a substitute of the LSTM layer launched within the earlier part, you’ll use the GRU layer, developed by Chung et al. in 2014. Gated recurrent unit (GRU) layers work utilizing the identical precept as LSTM, however they’re considerably streamlined and thus cheaper to run (though they might not have as a lot representational energy as LSTM). This trade-off between computational expensiveness and representational energy is seen all over the place in machine studying.

mannequin <- keras_model_sequential() %>%

layer_gru(models = 32, input_shape = checklist(NULL, dim(information)[[-1]])) %>%

layer_dense(models = 1)

mannequin %>% compile(

optimizer = optimizer_rmsprop(),

loss = "mae"

)

historical past <- mannequin %>% fit_generator(

train_gen,

steps_per_epoch = 500,

epochs = 20,

validation_data = val_gen,

validation_steps = val_steps

)The outcomes are plotted under. A lot better! You’ll be able to considerably beat the common sense baseline, demonstrating the worth of machine studying in addition to the prevalence of recurrent networks in comparison with sequence-flattening dense networks on this sort of job.

The brand new validation MAE of ~0.265 (earlier than you begin considerably overfitting) interprets to a imply absolute error of two.35˚C after denormalization. That’s a stable achieve on the preliminary error of two.57˚C, however you in all probability nonetheless have a little bit of a margin for enchancment.

Utilizing recurrent dropout to battle overfitting

It’s evident from the coaching and validation curves that the mannequin is overfitting: the coaching and validation losses begin to diverge significantly after a couple of epochs. You’re already conversant in a basic method for combating this phenomenon: dropout, which randomly zeros out enter models of a layer as a way to break happenstance correlations within the coaching information that the layer is uncovered to. However the best way to appropriately apply dropout in recurrent networks isn’t a trivial query. It has lengthy been recognized that making use of dropout earlier than a recurrent layer hinders studying reasonably than serving to with regularization. In 2015, Yarin Gal, as a part of his PhD thesis on Bayesian deep studying, decided the right approach to make use of dropout with a recurrent community: the identical dropout masks (the identical sample of dropped models) ought to be utilized at each timestep, as an alternative of a dropout masks that varies randomly from timestep to timestep. What’s extra, as a way to regularize the representations shaped by the recurrent gates of layers comparable to layer_gru and layer_lstm, a temporally fixed dropout masks ought to be utilized to the inside recurrent activations of the layer (a recurrent dropout masks). Utilizing the identical dropout masks at each timestep permits the community to correctly propagate its studying error by way of time; a temporally random dropout masks would disrupt this error sign and be dangerous to the training course of.

Yarin Gal did his analysis utilizing Keras and helped construct this mechanism straight into Keras recurrent layers. Each recurrent layer in Keras has two dropout-related arguments: dropout, a float specifying the dropout charge for enter models of the layer, and recurrent_dropout, specifying the dropout charge of the recurrent models. Let’s add dropout and recurrent dropout to the layer_gru and see how doing so impacts overfitting. As a result of networks being regularized with dropout all the time take longer to completely converge, you’ll prepare the community for twice as many epochs.

mannequin <- keras_model_sequential() %>%

layer_gru(models = 32, dropout = 0.2, recurrent_dropout = 0.2,

input_shape = checklist(NULL, dim(information)[[-1]])) %>%

layer_dense(models = 1)

mannequin %>% compile(

optimizer = optimizer_rmsprop(),

loss = "mae"

)

historical past <- mannequin %>% fit_generator(

train_gen,

steps_per_epoch = 500,

epochs = 40,

validation_data = val_gen,

validation_steps = val_steps

)The plot under exhibits the outcomes. Success! You’re not overfitting in the course of the first 20 epochs. However though you might have extra secure analysis scores, your greatest scores aren’t a lot decrease than they have been beforehand.

Stacking recurrent layers

Since you’re not overfitting however appear to have hit a efficiency bottleneck, you need to think about rising the capability of the community. Recall the outline of the common machine-learning workflow: it’s typically a good suggestion to extend the capability of your community till overfitting turns into the first impediment (assuming you’re already taking fundamental steps to mitigate overfitting, comparable to utilizing dropout). So long as you aren’t overfitting too badly, you’re doubtless below capability.

Rising community capability is often accomplished by rising the variety of models within the layers or including extra layers. Recurrent layer stacking is a basic method to construct more-powerful recurrent networks: for example, what presently powers the Google Translate algorithm is a stack of seven giant LSTM layers – that’s big.

To stack recurrent layers on high of one another in Keras, all intermediate layers ought to return their full sequence of outputs (a 3D tensor) reasonably than their output on the final timestep. That is accomplished by specifying return_sequences = TRUE.

mannequin <- keras_model_sequential() %>%

layer_gru(models = 32,

dropout = 0.1,

recurrent_dropout = 0.5,

return_sequences = TRUE,

input_shape = checklist(NULL, dim(information)[[-1]])) %>%

layer_gru(models = 64, activation = "relu",

dropout = 0.1,

recurrent_dropout = 0.5) %>%

layer_dense(models = 1)

mannequin %>% compile(

optimizer = optimizer_rmsprop(),

loss = "mae"

)

historical past <- mannequin %>% fit_generator(

train_gen,

steps_per_epoch = 500,

epochs = 40,

validation_data = val_gen,

validation_steps = val_steps

)The determine under exhibits the outcomes. You’ll be able to see that the added layer does enhance the outcomes a bit, although not considerably. You’ll be able to draw two conclusions:

- Since you’re nonetheless not overfitting too badly, you would safely improve the scale of your layers in a quest for validation-loss enchancment. This has a non-negligible computational price, although.

- Including a layer didn’t assist by a big issue, so it’s possible you’ll be seeing diminishing returns from rising community capability at this level.

Utilizing bidirectional RNNs

The final method launched on this part is named bidirectional RNNs. A bidirectional RNN is a typical RNN variant that may supply better efficiency than an everyday RNN on sure duties. It’s ceaselessly utilized in natural-language processing – you would name it the Swiss Military knife of deep studying for natural-language processing.

RNNs are notably order dependent, or time dependent: they course of the timesteps of their enter sequences so as, and shuffling or reversing the timesteps can fully change the representations the RNN extracts from the sequence. That is exactly the rationale they carry out properly on issues the place order is significant, such because the temperature-forecasting downside. A bidirectional RNN exploits the order sensitivity of RNNs: it consists of utilizing two common RNNs, such because the layer_gru and layer_lstm you’re already conversant in, every of which processes the enter sequence in a single route (chronologically and antichronologically), after which merging their representations. By processing a sequence each methods, a bidirectional RNN can catch patterns which may be ignored by a unidirectional RNN.

Remarkably, the truth that the RNN layers on this part have processed sequences in chronological order (older timesteps first) might have been an arbitrary choice. Not less than, it’s a call we made no try to query to date. May the RNNs have carried out properly sufficient in the event that they processed enter sequences in antichronological order, for example (newer timesteps first)? Let’s do this in apply and see what occurs. All that you must do is write a variant of the info generator the place the enter sequences are reverted alongside the time dimension (change the final line with checklist(samples[,ncol(samples):1,], targets)). Coaching the identical one-GRU-layer community that you simply used within the first experiment on this part, you get the outcomes proven under.

The reversed-order GRU underperforms even the common sense baseline, indicating that on this case, chronological processing is vital to the success of your method. This makes excellent sense: the underlying GRU layer will sometimes be higher at remembering the current previous than the distant previous, and naturally the more moderen climate information factors are extra predictive than older information factors for the issue (that’s what makes the common sense baseline pretty robust). Thus the chronological model of the layer is certain to outperform the reversed-order model. Importantly, this isn’t true for a lot of different issues, together with pure language: intuitively, the significance of a phrase in understanding a sentence isn’t normally depending on its place within the sentence. Let’s attempt the identical trick on the LSTM IMDB instance from part 6.2.

library(keras)

# Variety of phrases to think about as options

max_features <- 10000

# Cuts off texts after this variety of phrases

maxlen <- 500

imdb <- dataset_imdb(num_words = max_features)

c(c(x_train, y_train), c(x_test, y_test)) %<-% imdb

# Reverses sequences

x_train <- lapply(x_train, rev)

x_test <- lapply(x_test, rev)

# Pads sequences

x_train <- pad_sequences(x_train, maxlen = maxlen) <4>

x_test <- pad_sequences(x_test, maxlen = maxlen)

mannequin <- keras_model_sequential() %>%

layer_embedding(input_dim = max_features, output_dim = 128) %>%

layer_lstm(models = 32) %>%

layer_dense(models = 1, activation = "sigmoid")

mannequin %>% compile(

optimizer = "rmsprop",

loss = "binary_crossentropy",

metrics = c("acc")

)

historical past <- mannequin %>% match(

x_train, y_train,

epochs = 10,

batch_size = 128,

validation_split = 0.2

)You get efficiency practically equivalent to that of the chronological-order LSTM. Remarkably, on such a textual content dataset, reversed-order processing works simply in addition to chronological processing, confirming the

speculation that, though phrase order does matter in understanding language, which order you utilize isn’t essential. Importantly, an RNN skilled on reversed sequences will study totally different representations than one skilled on the unique sequences, a lot as you’d have totally different psychological fashions if time flowed backward in the true world – in the event you lived a life the place you died in your first day and have been born in your final day. In machine studying, representations which might be totally different but helpful are all the time value exploiting, and the extra they differ, the higher: they provide a unique approach from which to take a look at your information, capturing features of the info that have been missed by different approaches, and thus they might help enhance efficiency on a job. That is the instinct behind ensembling, an idea we’ll discover in chapter 7.

A bidirectional RNN exploits this concept to enhance on the efficiency of chronological-order RNNs. It seems to be at its enter sequence each methods, acquiring doubtlessly richer representations and capturing patterns that will have been missed by the chronological-order model alone.

To instantiate a bidirectional RNN in Keras, you utilize the bidirectional() perform, which takes a recurrent layer occasion as an argument. The bidirectional() perform creates a second, separate occasion of this recurrent layer and makes use of one occasion for processing the enter sequences in chronological order and the opposite occasion for processing the enter sequences in reversed order. Let’s attempt it on the IMDB sentiment-analysis job.

mannequin <- keras_model_sequential() %>%

layer_embedding(input_dim = max_features, output_dim = 32) %>%

bidirectional(

layer_lstm(models = 32)

) %>%

layer_dense(models = 1, activation = "sigmoid")

mannequin %>% compile(

optimizer = "rmsprop",

loss = "binary_crossentropy",

metrics = c("acc")

)

historical past <- mannequin %>% match(

x_train, y_train,

epochs = 10,

batch_size = 128,

validation_split = 0.2

)It performs barely higher than the common LSTM you tried within the earlier part, attaining over 89% validation accuracy. It additionally appears to overfit extra rapidly, which is unsurprising as a result of a bidirectional layer has twice as many parameters as a chronological LSTM. With some regularization, the bidirectional method would doubtless be a powerful performer on this job.

Now let’s attempt the identical method on the temperature prediction job.

mannequin <- keras_model_sequential() %>%

bidirectional(

layer_gru(models = 32), input_shape = checklist(NULL, dim(information)[[-1]])

) %>%

layer_dense(models = 1)

mannequin %>% compile(

optimizer = optimizer_rmsprop(),

loss = "mae"

)

historical past <- mannequin %>% fit_generator(

train_gen,

steps_per_epoch = 500,

epochs = 40,

validation_data = val_gen,

validation_steps = val_steps

)This performs about in addition to the common layer_gru. It’s simple to grasp why: all of the predictive capability should come from the chronological half of the community, as a result of the antichronological half is thought to be severely underperforming on this job (once more, as a result of the current previous issues way more than the distant previous on this case).

Going even additional

There are a lot of different issues you would attempt, as a way to enhance efficiency on the temperature-forecasting downside:

- Alter the variety of models in every recurrent layer within the stacked setup. The present decisions are largely arbitrary and thus in all probability suboptimal.

- Alter the training charge utilized by the

RMSpropoptimizer. - Attempt utilizing

layer_lstmas an alternative oflayer_gru. - Attempt utilizing a much bigger densely linked regressor on high of the recurrent layers: that’s, a much bigger dense layer or perhaps a stack of dense layers.

- Don’t overlook to finally run the best-performing fashions (by way of validation MAE) on the take a look at set! In any other case, you’ll develop architectures which might be overfitting to the validation set.

As all the time, deep studying is extra an artwork than a science. We will present tips that counsel what’s prone to work or not work on a given downside, however, in the end, each downside is exclusive; you’ll have to judge totally different methods empirically. There may be presently no idea that may let you know prematurely exactly what you need to do to optimally resolve an issue. You should iterate.

Wrapping up

Right here’s what you need to take away from this part:

- As you first discovered in chapter 4, when approaching a brand new downside, it’s good to first set up commonsense baselines in your metric of alternative. When you don’t have a baseline to beat, you possibly can’t inform whether or not you’re making actual progress.

- Attempt easy fashions earlier than costly ones, to justify the extra expense. Typically a easy mannequin will transform your best choice.

- When you might have information the place temporal ordering issues, recurrent networks are a fantastic match and simply outperform fashions that first flatten the temporal information.

- To make use of dropout with recurrent networks, you need to use a time-constant dropout masks and recurrent dropout masks. These are constructed into Keras recurrent layers, so all you need to do is use the

dropoutandrecurrent_dropoutarguments of recurrent layers. - Stacked RNNs present extra representational energy than a single RNN layer. They’re additionally way more costly and thus not all the time value it. Though they provide clear positive factors on advanced issues (comparable to machine translation), they might not all the time be related to smaller, less complicated issues.

- Bidirectional RNNs, which take a look at a sequence each methods, are helpful on natural-language processing issues. However they aren’t robust performers on sequence information the place the current previous is way more informative than the start of the sequence.

NOTE: Markets and machine studying

Some readers are certain to wish to take the strategies we’ve launched right here and check out them on the issue of forecasting the longer term worth of securities on the inventory market (or forex alternate charges, and so forth). Markets have very totally different statistical traits than pure phenomena comparable to climate patterns. Making an attempt to make use of machine studying to beat markets, if you solely have entry to publicly out there information, is a troublesome endeavor, and also you’re prone to waste your time and sources with nothing to point out for it.

At all times do not forget that in the case of markets, previous efficiency is not a great predictor of future returns – trying within the rear-view mirror is a foul method to drive. Machine studying, however, is relevant to datasets the place the previous is a great predictor of the longer term.