It will be difficult to call an American literary and social critic about whom extra nonsense has been written than Irving Babbitt (1865–1933). Babbitt, a classically skilled professor of French and comparative literature at Harvard College, was, alongside together with his greatest buddy and mental ally Paul Elmer Extra (1864–1937), one of many founding fathers of the New Humanism, a casual motion that attracted widespread consideration within the late Twenties and early Thirties.

The sudden and unanticipated fame accorded to the New Humanism in each the USA and Europe—ultimately even in China—inspired quite a few tradition warriors to weigh in on Babbitt, Extra, and their epigones. Their estimations, seemingly composed with the rapidity required of day by day newspapers and weekly magazines, contained all method of infelicities and distortions. Regardless of the manifest inaccuracies within the polemics in opposition to the New Humanism, Babbitt’s status has by some means by no means absolutely recovered from the raucous debates about his work. By the years, writers as varied as Allen Tate, Edmund Wilson, R. P. Blackmur, Alfred Kazin, and Edward Mentioned have pilloried Babbitt, and although their critiques go away a lot to be desired, their collective efforts seem to have denied him the lofty status that he deserves.

To make sure, Babbitt’s astoundingly capacious mind and meandering prose type contributed to misunderstandings about his concepts. Babbitt’s learnedness was legendary even within the halls of Harvard. In March of 1931, for instance, Time journal reported on a playing pool established by college students in Babbitt’s Comparative Literature 11 course, based on which members would place wagers primarily based on the (massive) variety of authors to whom Babbitt would refer in a lecture. In the future, Time famous, Babbitt “set a file: 73 quotations, from writers so varied as St. Paul, Confucius, Dante, [and] Walter Lippmann.” A lifelong critic of triflingly minute analysis, Babbitt refused to cut back his writings to the diktats of professionalized scholarship. Particularly for the narrowly skilled teachers of his (and our) period, Babbitt’s broad studying might go away critics feeling out of their depth.

Regardless of his spectacular mental presents, Babbitt—who, based on a lot of his mates and former college students, was naturally extra of a talker than a author—had issue envisioning readers who hadn’t accrued his huge data. Accordingly, his books don’t proceed in a typical systematic trend, scaffolding arguments in logical sequences to maximise their intelligibility. As a substitute, readers should muddle via Babbitt’s sprawling works to cobble collectively the fundamentals of his arguments. Regardless of excelling at offering punchy, typically humorous, phrases and quotable quips, Babbitt is a demanding creator.

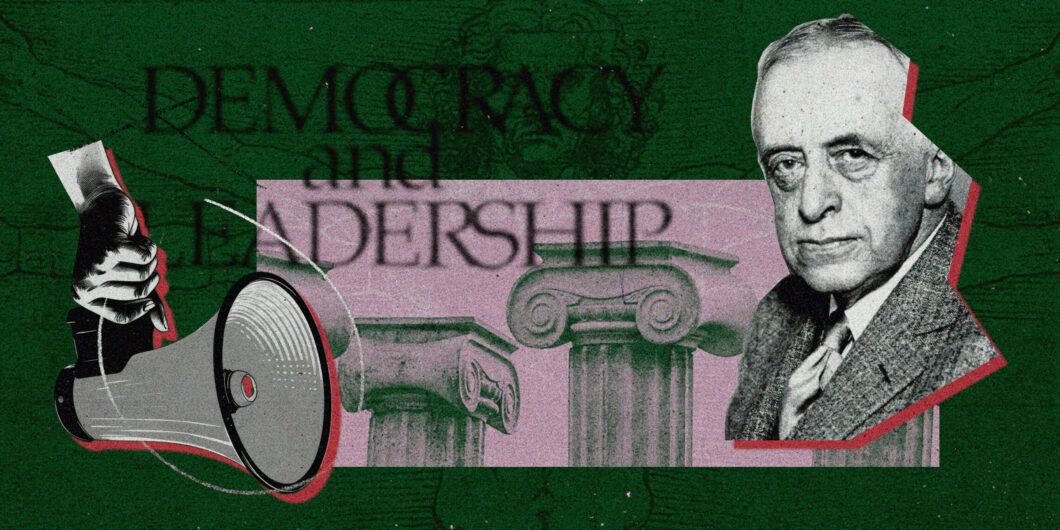

Given the hindrances that face all who method Babbitt’s prose, Allen Mendenhall must be praised for offering a concise and considerate examination of Democracy and Management, Babbitt’s lone book-length contribution to political concept. Though I’ve some disagreements with Mendenhall’s evaluation (extra on this anon), he’s the form of interlocutor whom Babbitt deserves (however has solely seldom obtained). In actual fact, Mendenhall’s essay provides us a way of why Babbitt’s output—regardless of its manifest challenges—continues to deserve a large readership at present.

Opposite to many years of cavalier conclusions about Babbitt’s spiritual views, it’s clear that he didn’t think about the New Humanism to be inimical to religion.

It’s among the many strengths of Mendenhall’s essay that it shares Babbitt’s sense of urgency and relates Democracy and Management to our present political second. It could appear churlish to notice reservations about an essay that gives a lot with which to assent, however I hope the evaluation to comply with will assist flesh out Babbitt’s method to political concept and the human predicament.

Early in his piece, Mendenhall supplies a couple of ideas he deems integral to Babbitt’s thought. Absent is the time period most important to the New Humanism’s model of moral dualism: the interior verify. This idea, which Babbitt additionally known as the “greater will” and (in a riposte to the French thinker Henri Bergson) the frein important, is central to Babbitt’s definition of humanism and to his all-important critique of what he calls “sentimental” and “scientific” naturalism. An incapacity to know Babbitt’s that means on this level and to acknowledge its nice significance has incapacitated a lot of his critics.

In Rousseau and Romanticism (1919), the monograph he composed instantly earlier than Democracy and Management, Babbitt describes the interior verify thus:

Like all the good Greeks, Aristotle acknowledges that man is the creature of two legal guidelines: he has an extraordinary or pure self of impulse and want and a human self that’s identified virtually as an influence of management over impulse and want. If man is to develop into human he should not let impulse and want run wild, however should oppose to every part extreme in his extraordinary self, whether or not in thought or deed or emotion, the legislation of measure.

In keeping with Babbitt, who spied an affirmation of the interior verify in traditions as disparate as Greek philosophy, Hinduism, Confucianism, Buddhism, and Christianity, individuals should interact their “human self”—their inside energy of management—to affirm these impulses conducive to respectful and civilized life and to quash these which might be egocentric and damaging. Babbitt views this ordering drive as transcending subjectivity. All the time ecumenical relating to the final word questions, he sees this particular kind of will as ultimately acknowledged by all the upper world religions and moral methods. Though representing a constructive objective, it will is felt, close to impulses which might be damaging of goodness on this planet, as a “will to chorus,” a verify. This greater will in man is, based on Babbitt, what Christianity calls “Grace.”

Due to the unlucky dominance of naturalism—the rejection of a common ethical crucial—in his day, Babbitt thought, human beings usually eschewed this “civil struggle within the cave,” preferring, because the Rousseauian sentimentalist endorsed, to enjoy dreamy impulse or, because the Baconian utilitarian suggested, to realize growing mastery over the pure world. Though not unreceptive to the advantages of the romantic motion and the scientific challenge, Babbitt acknowledged that the avoidance of the interior wrestle between good and evil—what Babbitt in Democracy and Management known as “the previous dualism”—would courtroom private distress and civilizational chaos. “The previous dualism put the battle between good and evil within the breast of the person,” Babbitt wrote, “with evil so predominant because the Fall that it behooves man to be humble; with Rousseau, this battle is transferred from the person to society.” The scientific naturalist analogously locations the emphasis on manipulation of the exterior world.

Babbitt’s perspective on ethics pertains on to his method to political concept. Readers of Mendenhall’s essay could conclude that Babbitt was by some means anti-democratic, a fusty aristocrat appalled by the good unwashed. This view—frequent among the many tradition warriors who’ve attacked Babbitt—is mistaken. Democracy has no single definition. Because the political thinker Claes G. Ryn has persuasively argued, Babbitt opposes a sure method to in style rule whereas supporting one other. In his ebook Democracy and the Moral Life (1978), for instance, Ryn, drawing on Babbitt, makes a distinction between two very completely different types of in style authorities: majoritarian/plebiscitary democracy and constitutional/consultant democracy.

Babbitt’s Democracy and Management supplies a critique of the previous and assist for the latter. His rationale for this place pertains to the idea of the interior verify: in Rousseauistic type, plebiscitary democracy depends on the instantaneous impulses of the individuals, whereas constitutional democracy provides wanted checks on energy—together with in style energy. The checks and balances key to the US Structure, then, are a form of governmental corollary to an individual’s frein important. Babbitt thought of plebiscitary democracy harmful—and finally imperialistic—as a result of it stemmed from the form of unrealistic view of human nature he attributed to sentimental naturalism.

Different frequent misconceptions about Babbitt’s concepts encompass his method to faith and the way it pertains to humanism. Babbitt arguably brought on some such misimpressions; non-confessional in faith and an admirer of features of Buddhism, he was typically cagey in his books and essays in regards to the relationship between his experiential method to the final word questions and doctrinally primarily based notions of religion. Even Paul Elmer Extra, upon his return to Christianity within the late 1910s, criticized Babbitt for his supposed vagueness in regards to the exact that means of the “superhuman” and the “supernatural.”

But Mendenhall errs when he states that “Babbitt’s humanism embraces company and can whereas the naturalistic and spiritual modes undergo from determinism or fatalism.” Right here once more Ryn—for many years Babbitt’s most dependable and incisive interpreter—will help us keep away from confusion. In a bit known as “Irving Babbitt and the Christians,” Ryn notes, “In formulating the thought of the interior verify, or greater will, Babbitt isn’t attempting to speak Christians out of their beliefs. He’s addressing all of these within the fashionable world who should not prepared to just accept moral and spiritual fact on the authority of inherited dogmas. To those fashionable skeptics, he argues, not that conventional beliefs are flawed, however that moral and spiritual life don’t stand and fall with Church authority. They’ve an experiential basis.”

Though Babbitt believed that spiritual modes of thought might undergo from determinism and fatalism, this was under no circumstances a foregone conclusion. In actual fact, all through Democracy and Management, Babbitt proves supportive of sure Christian, Buddhist, and even Islamic conceptions of religion. Babbitt made his assist for faith even clearer in his contribution to Norman Foerster’s edited assortment Humanism and America (1930): “For my very own half,” he wrote, “I vary myself unhesitatingly on the facet of the supernaturalists. Although I see no proof that humanism is essentially ineffective other than dogmatic and revealed faith, there’s, because it appears to me, proof that it positive factors immensely in effectiveness when it has a background in spiritual perception.” Opposite to many years of cavalier conclusions about Babbitt’s spiritual views, it’s clear that he didn’t think about the New Humanism to be inimical to religion. His method to the final word questions was, quite the opposite, an try to restate and get better in experiential phrases moral-spiritual insights that have been being misplaced underneath the sway of scientific and nostalgic naturalism.

I wholeheartedly agree with Mendenhall when he concludes that Babbitt’s “beliefs and convictions” nonetheless “stay related. And we’re mistaken and misguided to disregard them.” We could hope that the one centesimal anniversary of Democracy and Management will encourage readers to look at Babbitt’s concepts anew.