About half a 12 months in the past, this weblog featured a publish, written by Daniel Falbel, on tips on how to use Keras to categorise items of spoken language. The article acquired loads of consideration and never surprisingly, questions arose tips on how to apply that code to totally different datasets. We’ll take this as a motivation to discover in additional depth the preprocessing completed in that publish: If we all know why the enter to the community seems the best way it seems, we will modify the mannequin specification appropriately if want be.

In case you’ve a background in speech recognition, and even normal sign processing, for you the introductory a part of this publish will in all probability not comprise a lot information. Nonetheless, you would possibly nonetheless have an interest within the code half, which reveals tips on how to do issues like creating spectrograms with present variations of TensorFlow.

In the event you don’t have that background, we’re inviting you on a (hopefully) fascinating journey, barely pertaining to one of many higher mysteries of this universe.

We’ll use the identical dataset as Daniel did in his publish, that’s, model 1 of the Google speech instructions dataset(Warden 2018)

The dataset consists of ~ 65,000 WAV recordsdata, of size one second or much less. Every file is a recording of considered one of thirty phrases, uttered by totally different audio system.

The purpose then is to coach a community to discriminate between spoken phrases. How ought to the enter to the community look? The WAV recordsdata comprise amplitudes of sound waves over time. Listed below are a couple of examples, akin to the phrases chicken, down, sheila, and visible:

A sound wave is a sign extending in time, analogously to how what enters our visible system extends in house.

At every cut-off date, the present sign relies on its previous. The apparent structure to make use of in modeling it thus appears to be a recurrent neural community.

Nonetheless, the data contained within the sound wave may be represented in another method: specifically, utilizing the frequencies that make up the sign.

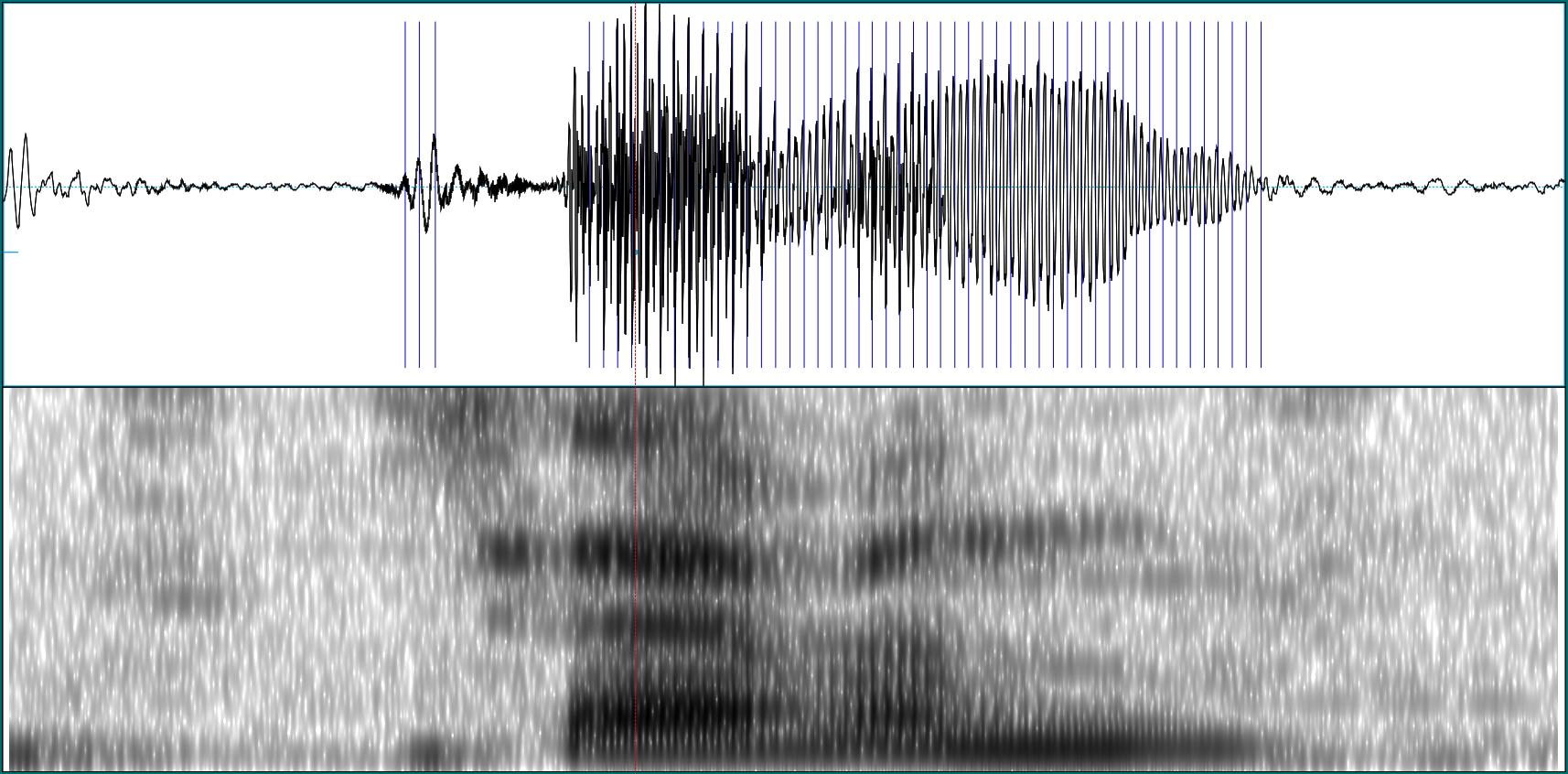

Right here we see a sound wave (high) and its frequency illustration (backside).

Within the time illustration (known as the time area), the sign consists of consecutive amplitudes over time. Within the frequency area, it’s represented as magnitudes of various frequencies. It could seem as one of many best mysteries on this world that you would be able to convert between these two with out lack of info, that’s: Each representations are basically equal!

Conversion from the time area to the frequency area is finished utilizing the Fourier remodel; to transform again, the Inverse Fourier Remodel is used. There exist various kinds of Fourier transforms relying on whether or not time is considered as steady or discrete, and whether or not the sign itself is steady or discrete. Within the “actual world,” the place often for us, actual means digital as we’re working with digitized alerts, the time area in addition to the sign are represented as discrete and so, the Discrete Fourier Remodel (DFT) is used. The DFT itself is computed utilizing the FFT (Quick Fourier Remodel) algorithm, leading to vital speedup over a naive implementation.

Trying again on the above instance sound wave, it’s a compound of 4 sine waves, of frequencies 8Hz, 16Hz, 32Hz, and 64Hz, whose amplitudes are added and displayed over time. The compound wave right here is assumed to increase infinitely in time. In contrast to speech, which modifications over time, it may be characterised by a single enumeration of the magnitudes of the frequencies it’s composed of. So right here the spectrogram, the characterization of a sign by magnitudes of constituent frequencies various over time, seems basically one-dimensional.

Nonetheless, once we ask Praat to create a spectrogram of considered one of our instance sounds (a seven), it may appear to be this:

Right here we see a two-dimensional picture of frequency magnitudes over time (greater magnitudes indicated by darker coloring). This two-dimensional illustration could also be fed to a community, rather than the one-dimensional amplitudes. Accordingly, if we resolve to take action we’ll use a convnet as a substitute of an RNN.

Spectrograms will look totally different relying on how we create them. We’ll check out the important choices in a minute. First although, let’s see what we can’t at all times do: ask for all frequencies that had been contained within the analog sign.

Above, we stated that each representations, time area and frequency area, had been basically equal. In our digital actual world, that is solely true if the sign we’re working with has been digitized appropriately, or as that is generally phrased, if it has been “correctly sampled.”

Take speech for example: As an analog sign, speech per se is steady in time; for us to have the ability to work with it on a pc, it must be transformed to occur in discrete time. This conversion of the unbiased variable (time in our case, house in e.g. picture processing) from steady to discrete known as sampling.

On this means of discretization, a vital choice to be made is the sampling charge to make use of. The sampling charge must be at the very least double the best frequency within the sign. If it’s not, lack of info will happen. The way in which that is most frequently put is the opposite method spherical: To protect all info, the analog sign could not comprise frequencies above one-half the sampling charge. This frequency – half the sampling charge – known as the Nyquist charge.

If the sampling charge is simply too low, aliasing takes place: Increased frequencies alias themselves as decrease frequencies. Which means not solely can’t we get them, in addition they corrupt the magnitudes of corresponding decrease frequencies they’re being added to.

Right here’s a schematic instance of how a high-frequency sign may alias itself as being lower-frequency. Think about the high-frequency wave being sampled at integer factors (gray circles) solely:

Within the case of the speech instructions dataset, all sound waves have been sampled at 16 kHz. Which means once we ask Praat for a spectogram, we must always not ask for frequencies greater than 8kHz. Here’s what occurs if we ask for frequencies as much as 16kHz as a substitute – we simply don’t get them:

Now let’s see what choices we do have when creating spectrograms.

Within the above easy sine wave instance, the sign stayed fixed over time. Nonetheless in speech utterances, the magnitudes of constituent frequencies change over time. Ideally thus, we’d have a precise frequency illustration for each cut-off date. As an approximation to this perfect, the sign is split into overlapping home windows, and the Fourier remodel is computed for every time slice individually. That is known as the Quick Time Fourier Remodel (STFT).

After we compute the spectrogram by way of the STFT, we have to inform it what measurement home windows to make use of, and the way huge to make the overlap. The longer the home windows we use, the higher the decision we get within the frequency area. Nonetheless, what we acquire in decision there, we lose within the time area, as we’ll have fewer home windows representing the sign. It is a normal precept in sign processing: Decision within the time and frequency domains are inversely associated.

To make this extra concrete, let’s once more have a look at a easy instance. Right here is the spectrogram of an artificial sine wave, composed of two parts at 1000 Hz and 1200 Hz. The window size was left at its (Praat) default, 5 milliseconds:

We see that with a brief window like that, the 2 totally different frequencies are mangled into one within the spectrogram.

Now enlarge the window to 30 milliseconds, and they’re clearly differentiated:

The above spectrogram of the phrase “seven” was produced utilizing Praats default of 5 milliseconds. What occurs if we use 30 milliseconds as a substitute?

We get higher frequency decision, however on the worth of decrease decision within the time area. The window size used throughout preprocessing is a parameter we’d wish to experiment with later, when coaching a community.

One other enter to the STFT to play with is the kind of window used to weight the samples in a time slice. Right here once more are three spectrograms of the above recording of seven, utilizing, respectively, a Hamming, a Hann, and a Gaussian window:

Whereas the spectrograms utilizing the Hann and Gaussian home windows don’t look a lot totally different, the Hamming window appears to have launched some artifacts.

Preprocessing choices don’t finish with the spectrogram. A preferred transformation utilized to the spectrogram is conversion to mel scale, a scale based mostly on how people really understand variations in pitch. We don’t elaborate additional on this right here, however we do briefly touch upon the respective TensorFlow code under, in case you’d wish to experiment with this.

Previously, coefficients remodeled to Mel scale have typically been additional processed to acquire the so-called Mel-Frequency Cepstral Coefficients (MFCCs). Once more, we simply present the code. For glorious studying on Mel scale conversion and MFCCs (together with the explanation why MFCCs are much less typically used these days) see this publish by Haytham Fayek.

Again to our authentic process of speech classification. Now that we’ve gained a little bit of perception in what’s concerned, let’s see tips on how to carry out these transformations in TensorFlow.

Code will likely be represented in snippets in response to the performance it offers, so we could immediately map it to what was defined conceptually above.

A whole instance is out there right here. The entire instance builds on Daniel’s authentic code as a lot as attainable, with two exceptions:

-

The code runs in keen in addition to in static graph mode. In the event you resolve you solely ever want keen mode, there are a couple of locations that may be simplified. That is partly associated to the truth that in keen mode, TensorFlow operations rather than tensors return values, which we will immediately cross on to TensorFlow features anticipating values, not tensors. As well as, much less conversion code is required when manipulating intermediate values in R.

-

With TensorFlow 1.13 being launched any day, and preparations for TF 2.0 working at full pace, we wish the code to necessitate as few modifications as attainable to run on the following main model of TF. One huge distinction is that there’ll not be a

contribmodule. Within the authentic publish,contribwas used to learn within the.wavrecordsdata in addition to compute the spectrograms. Right here, we’ll use performance fromtf.audioandtf.signas a substitute.

All operations proven under will run inside tf.dataset code, which on the R aspect is achieved utilizing the tfdatasets package deal.

To clarify the person operations, we have a look at a single file, however later we’ll additionally show the information generator as a complete.

For stepping by means of particular person traces, it’s at all times useful to have keen mode enabled, independently of whether or not finally we’ll execute in keen or graph mode:

We decide a random .wav file and decode it utilizing tf$audio$decode_wav.This can give us entry to 2 tensors: the samples themselves, and the sampling charge.

fname <- "information/speech_commands_v0.01/chicken/00b01445_nohash_0.wav"

wav <- tf$audio$decode_wav(tf$read_file(fname))wav$sample_rate accommodates the sampling charge. As anticipated, it’s 16000, or 16kHz:

sampling_rate <- wav$sample_rate %>% as.numeric()

sampling_rate16000The samples themselves are accessible as wav$audio, however their form is (16000, 1), so we’ve to transpose the tensor to get the same old (batch_size, variety of samples) format we’d like for additional processing.

samples <- wav$audio

samples <- samples %>% tf$transpose(perm = c(1L, 0L))

samplestf.Tensor(

[[-0.00750732 0.04653931 0.02041626 ... -0.01004028 -0.01300049

-0.00250244]], form=(1, 16000), dtype=float32)Computing the spectogram

To compute the spectrogram, we use tf$sign$stft (the place stft stands for Quick Time Fourier Remodel). stft expects three non-default arguments: Moreover the enter sign itself, there are the window measurement, frame_length, and the stride to make use of when figuring out the overlapping home windows, frame_step. Each are expressed in models of variety of samples. So if we resolve on a window size of 30 milliseconds and a stride of 10 milliseconds …

window_size_ms <- 30

window_stride_ms <- 10… we arrive on the following name:

samples_per_window <- sampling_rate * window_size_ms/1000

stride_samples <- sampling_rate * window_stride_ms/1000

stft_out <- tf$sign$stft(

samples,

frame_length = as.integer(samples_per_window),

frame_step = as.integer(stride_samples)

)Inspecting the tensor we acquired again, stft_out, we see, for our single enter wave, a matrix of 98 x 257 advanced values:

tf.Tensor(

[[[ 1.03279948e-04+0.00000000e+00j -1.95371482e-04-6.41121820e-04j

-1.60833192e-03+4.97534114e-04j ... -3.61620914e-05-1.07343149e-04j

-2.82576875e-05-5.88812982e-05j 2.66879797e-05+0.00000000e+00j]

...

]],

form=(1, 98, 257), dtype=complex64)Right here 98 is the variety of durations, which we will compute upfront, based mostly on the variety of samples in a window and the scale of the stride:

257 is the variety of frequencies we obtained magnitudes for. By default, stft will apply a Quick Fourier Remodel of measurement smallest energy of two higher or equal to the variety of samples in a window, after which return the fft_length / 2 + 1 distinctive parts of the FFT: the zero-frequency time period and the positive-frequency phrases.

In our case, the variety of samples in a window is 480. The closest enclosing energy of two being 512, we find yourself with 512/2 + 1 = 257 coefficients.

This too we will compute upfront:

Again to the output of the STFT. Taking the elementwise magnitude of the advanced values, we acquire an vitality spectrogram:

magnitude_spectrograms <- tf$abs(stft_out)If we cease preprocessing right here, we’ll often wish to log remodel the values to raised match the sensitivity of the human auditory system:

log_magnitude_spectrograms = tf$log(magnitude_spectrograms + 1e-6)Mel spectrograms and Mel-Frequency Cepstral Coefficients (MFCCs)

If as a substitute we select to make use of Mel spectrograms, we will acquire a change matrix that may convert the unique spectrograms to Mel scale:

lower_edge_hertz <- 0

upper_edge_hertz <- 2595 * log10(1 + (sampling_rate/2)/700)

num_mel_bins <- 64L

num_spectrogram_bins <- magnitude_spectrograms$form[-1]$worth

linear_to_mel_weight_matrix <- tf$sign$linear_to_mel_weight_matrix(

num_mel_bins,

num_spectrogram_bins,

sampling_rate,

lower_edge_hertz,

upper_edge_hertz

)Making use of that matrix, we acquire a tensor of measurement (batch_size, variety of durations, variety of Mel coefficients) which once more, we will log-compress if we wish:

mel_spectrograms <- tf$tensordot(magnitude_spectrograms, linear_to_mel_weight_matrix, 1L)

log_mel_spectrograms <- tf$log(mel_spectrograms + 1e-6)Only for completeness’ sake, lastly we present the TensorFlow code used to additional compute MFCCs. We don’t embody this within the full instance as with MFCCs, we would wish a special community structure.

num_mfccs <- 13

mfccs <- tf$sign$mfccs_from_log_mel_spectrograms(log_mel_spectrograms)[, , 1:num_mfccs]Accommodating different-length inputs

In our full instance, we decide the sampling charge from the primary file learn, thus assuming all recordings have been sampled on the identical charge. We do enable for various lengths although. For instance in our dataset, had we used this file, simply 0.65 seconds lengthy, for demonstration functions:

fname <- "information/speech_commands_v0.01/chicken/1746d7b6_nohash_0.wav"we’d have ended up with simply 63 durations within the spectrogram. As we’ve to outline a set input_size for the primary conv layer, we have to pad the corresponding dimension to the utmost attainable size, which is n_periods computed above.

The padding really takes place as a part of dataset definition. Let’s rapidly see dataset definition as a complete, leaving out the attainable technology of Mel spectrograms.

data_generator <- perform(df,

window_size_ms,

window_stride_ms) {

# assume sampling charge is identical in all samples

sampling_rate <-

tf$audio$decode_wav(tf$read_file(tf$reshape(df$fname[[1]], listing()))) %>% .$sample_rate

samples_per_window <- (sampling_rate * window_size_ms) %/% 1000L

stride_samples <- (sampling_rate * window_stride_ms) %/% 1000L

n_periods <-

tf$form(

tf$vary(

samples_per_window %/% 2L,

16000L - samples_per_window %/% 2L,

stride_samples

)

)[1] + 1L

n_fft_coefs <-

(2 ^ tf$ceil(tf$log(

tf$solid(samples_per_window, tf$float32)

) / tf$log(2)) /

2 + 1L) %>% tf$solid(tf$int32)

ds <- tensor_slices_dataset(df) %>%

dataset_shuffle(buffer_size = buffer_size)

ds <- ds %>%

dataset_map(perform(obs) {

wav <-

tf$audio$decode_wav(tf$read_file(tf$reshape(obs$fname, listing())))

samples <- wav$audio

samples <- samples %>% tf$transpose(perm = c(1L, 0L))

stft_out <- tf$sign$stft(samples,

frame_length = samples_per_window,

frame_step = stride_samples)

magnitude_spectrograms <- tf$abs(stft_out)

log_magnitude_spectrograms <- tf$log(magnitude_spectrograms + 1e-6)

response <- tf$one_hot(obs$class_id, 30L)

enter <- tf$transpose(log_magnitude_spectrograms, perm = c(1L, 2L, 0L))

listing(enter, response)

})

ds <- ds %>%

dataset_repeat()

ds %>%

dataset_padded_batch(

batch_size = batch_size,

padded_shapes = listing(tf$stack(listing(

n_periods, n_fft_coefs,-1L

)),

tf$fixed(-1L, form = form(1L))),

drop_remainder = TRUE

)

}The logic is identical as described above, solely the code has been generalized to work in keen in addition to graph mode. The padding is taken care of by dataset_padded_batch(), which must be advised the utmost variety of durations and the utmost variety of coefficients.

Time for experimentation

Constructing on the full instance, now could be the time for experimentation: How do totally different window sizes have an effect on classification accuracy? Does transformation to the mel scale yield improved outcomes? You may also wish to attempt passing a non-default window_fn to stft (the default being the Hann window) and see how that impacts the outcomes. And naturally, the easy definition of the community leaves loads of room for enchancment.

Talking of the community: Now that we’ve gained extra perception into what’s contained in a spectrogram, we’d begin asking, is a convnet actually an enough resolution right here? Usually we use convnets on pictures: two-dimensional information the place each dimensions characterize the identical form of info. Thus with pictures, it’s pure to have sq. filter kernels.

In a spectrogram although, the time axis and the frequency axis characterize essentially various kinds of info, and it isn’t clear in any respect that we must always deal with them equally. Additionally, whereas in pictures, the interpretation invariance of convnets is a desired characteristic, this isn’t the case for the frequency axis in a spectrogram.

Closing the circle, we uncover that as a consequence of deeper data in regards to the topic area, we’re in a greater place to purpose about (hopefully) profitable community architectures. We depart it to the creativity of our readers to proceed the search…