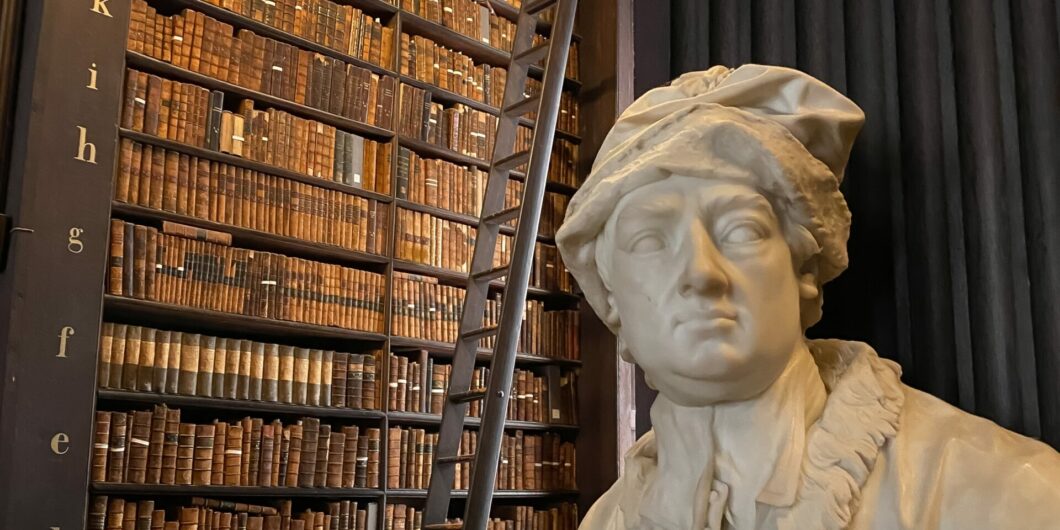

Historical past can shine gentle even within the unlikeliest of locations. What might seem like essentially the most fashionable and modern of issues might change into a mere echo of the previous. Faux information, disinformation, and social media could seem to pose strikingly new challenges without spending a dime speech—however regardless of the novelty of immediately’s progressive types of on-line communication, the problems are very removed from new. 300 years in the past, within the early eighteenth century, one of many biggest writers of English was worrying away on the implications of authorized and technological change for what had been then the emergent values of free speech. That author was Jonathan Swift.

Swift got here of age because the English lastly did away with the prior restraints that had inhibited and curtailed the press since its invention within the late Center Ages. Famously, the Licensing Act was allowed to lapse in England in 1695 (the 12 months by which Swift was ordained as a priest within the Anglican church). For the primary time, the press was uncensored. This didn’t imply that writers had been out of the blue free to print no matter they happy. Work that was hostile to the authorities or crucial of the federal government would appeal to the eye of prison legislation, with prosecutors being fast to cost writers, printers, and publishers alike with the offence of seditious libel. These convicted can be sentenced to face within the pillory. Swift, regardless of his brilliantly biting satire, managed one way or the other to keep away from this destiny, even when numerous his close to contemporaries weren’t so lucky. Daniel Defoe, for instance, was pilloried.

Actions for seditious libel, nevertheless, had been taken within the courts after the occasion—after the offending materials had already been revealed. From 1695 on, the press didn’t have to hunt anybody’s permission—anybody’s licence—earlier than it went to print. David Hume was removed from alone in celebrating this advance as if it meant Nice Britain was the freest nation in Europe: “Nothing is extra apt to shock a foreigner,” he boasted, “than the intense liberty, which we take pleasure in on this nation, of speaking no matter we please to the general public.”

Writing in the same vein within the 1760s, the nice English jurist Sir William Blackstone, in his Commentaries on the Legal guidelines of England, opined that:

The freedom of the press is … important to the character of a free state, however this consists in laying no earlier restraints upon publications, and never in freedom from censure for prison matter when revealed. Each freeman has an undoubted proper to put what sentiments he pleases earlier than the general public: to forbid that is to destroy the liberty of the press. But when he publishes what’s improper, mischievous or unlawful, he should take the consequence of his personal temerity.

Blackstone continued as follows:

to punish (because the legislation does at current) any harmful or offensive writings, which, when revealed, shall on a good and neutral trial be adjudged of a pernicious tendency, is important for the preservation of peace and good order, of presidency and faith, the one strong foundations of civil liberty. Thus the desire of people remains to be left free; the abuse solely of that free will is the thing of authorized punishment.

If that’s what handed for freedom of speech within the eighteenth century, our requirements immediately are extra exacting. Beneath the First Modification to the US Structure, for instance, Congress shall make no legislation abridging the liberty of speech. Solely the narrowest vary of exceptions is permitted. Speech so violent it quantities to “preventing phrases,” speech that’s obscene, or speech that’s defamatory could also be silenced, however the US Supreme Court docket has labored laborious since no less than the Nineteen Sixties to make sure that these exceptions are drawn as tightly as doable.

Not so for Blackstone. In his conclusions on the subject, Blackstone quotes approvingly an unnamed “high-quality author on this topic,” who says that “a person could also be allowed to maintain poisons in his closet, however not publicly to vend them as cordials.” That’s, even when within the 1760s the legislation now not anxious all that a lot about what males thought (throughout the privateness of their minds), as soon as they began making their views identified to the general public, they’d higher ensure that what they had been saying was healthful and never noxious. Blackstone doesn’t establish who his “high-quality author” was. However it’s Jonathan Swift—the citation is from Gulliver’s Travels (1726).

Two of Swift’s earlier works, The Battle of the Books and A Story of the Tub, revealed collectively in 1704 however written within the mid-1690s, gave voice to issues in regards to the implications without spending a dime speech which had been to stick with him for a lot of his profession, together with in his masterpiece, Gulliver’s Travels. The Battle of the Books is ostensibly a fable in regards to the ancients and the moderns. A Story of the Tub is a fancy piece of literary, political, and non secular satire, roughly not possible to classify however which, in the primary, could also be learn as an allegorical parable in regards to the growth of Christianity in Europe. Each items include a spread of prefaces, introductions, letters dedicatory, and digressions, by which Swift takes intention on the proliferation of “Grub Avenue” scribblers whose inferior works, after the lapsing of the Licensing Act, had been pouring in his view all too freely from the London presses.

In The Battle of the Books, he writes that:

ink is the nice missive weapon in all battles of the discovered, which, conveyed by way of a type of engine known as a quill, infinite numbers of those are darted on the enemy by the valiant on either side, with equal ability and violence, as if it had been an engagement of porcupines.

He imagines a personality, representing Criticism, along with her mother and father Ignorance and Pleasure sitting on both facet of her. Alongside them is her sister Opinion, “gentle of foot, hoodwinked, and headstrong, but giddy and perpetually turning.” In entrance of them play her kids, Noise and Impudence, Dullness and Vainness, Pedantry and Ailing-Manners. Criticism explains that:

Tis I who give knowledge to infants and idiots; by me, kids develop wiser than their mother and father; by me, beaux develop into politicians, and schoolboys judges of philosophy; by me, sophisters debate and conclude upon the depths of data; and coffeehouse wits, intuition by me, can right an writer’s type and show his minutest errors with out understanding a syllable of his matter or his language.

In an unlicensed age, any idiot could be a critic. Anybody can choose up a pen. Everybody has an opinion, irrespective of how hoodwinked or headstrong. And, to cap all of it, everybody has a megaphone.

The humour of Swift’s type mustn’t obscure the seriousness of his level. He was appalled by what he learn. As one commentator has put it, the top of licensing had created a “cultural swamp” by which “imaginations didn’t a lot soar as sink” and the place prose lacked all type, “like bilge.” The identical is claimed not of Grub Avenue however of social media. Twitter and its ilk are a swamp, by which bilge drowns out reality, and the place the noise is each countless and endlessly deceptive. Falsehood speeds across the globe whereas the reality remains to be tying up its bootstraps.

Swift had a deeper level. For it was not simply the “literary mediocrity” of Grub Avenue that irritated him: it was additionally that the brand new trend without spending a dime speech was based mostly on a profound error and that its penalties had been prone to be extremely harmful. The error, in Swift’s view, was to think about that what went for freedom of conscience ought to go likewise for freedom of speech.

If we would like free speech, we are going to simply should put up with its vices, its drawbacks and its inconveniences, faux information and disinformation included.

Swift, as now we have famous, was an Anglican—a theologian, an ordained priest, and, for thirty years, Dean of St Patrick’s in Dublin. He understood conscience to imply the “liberty of figuring out our personal ideas,” a liberty ”nobody can take from us.” Conscience, as such, was wholly inside—it “correctly signifies that data which a person hath inside himself of his personal ideas.” Swift was opposed solely to the ”fairly totally different” which means which, in his day, conscience had come to amass:

Liberty of Conscience is these days not solely understood to be the freedom of believing what males please, but in addition of endeavouring to propagate the idea as a lot as they will and to overthrow the religion which the legal guidelines have already established, to be rewarded by the general public for these depraved endeavours.

This, he mentioned, was the view of “fanatics” who, furthermore, present not the slightest ”public spirit or tenderness” to those that disagree with them.

The growth of liberty of conscience into freedom of speech was not solely an error for Swift: it was perilous. Particularly, it was hazardous to public order and the established authority of church and state. This was the hazard Swift alluded to in his preface to A Story of the Tub, the place he refers to “the wits of the current age being so very quite a few and penetrating, it appears the grandees of Church and State start to fall beneath horrible apprehensions.” Swift was aghast that the slightest murmur towards a minister of the Crown could lead on on to the pillory, whereas displaying “your utmost rhetoric towards mankind,” telling them “we’re all gone astray,” was thought to be the benign supply of ”valuable and helpful truths” irrespective of how destabilising it was to peace, order, and good authorities.

If these views had been Tory in character, it didn’t comply with that Swift thought the state might or ought to return to the previous methods of suppression. Swift knew which manner the tide was flowing and he was greater than astute sufficient to grasp that any official try to impede it could be futile. When he urged his pal, the editor of the Tatler journal “to utilize your authority as Censor, and by an annual index expurgatorius expunge all phrases and phrases which are offensive to good sense, and condemn these barbarous mutilations of vowels and syllables,” he knew full properly it was by no means going to occur.

The genie was out of the bottle, and there was no placing it again. The facility of the genie—the ability of free speech—could also be liberating. However it might additionally wreak havoc, bringing with it its handmaidens: criticism, ignorance, pleasure, and, worst of all, ill-formed opinion. Freedom had come at a value, and Swift spent many a protracted 12 months questioning whether or not it had been a value value paying. In E-book II of Gulliver’s Travels, Swift has the King of Brobdingnag inform Gulliver that:

he knew no purpose, why those that entertain opinions prejudicial to the general public, needs to be obliged to vary, or shouldn’t be obliged to hide them. And, because it was tyranny in any authorities to require the primary, so it was weak spot to not implement the second.

Because of this “a person could also be allowed to maintain poisons in his closet, however to not vend them about as cordials.”

Swift was removed from alone in his time in pondering this out loud. We’ve seen that he had Sir William Blackstone for firm. Likewise, he had Samuel Johnson. Take into account what Dr Johnson has to say, for instance, in his Lives of the Poets (1779), about Milton’s nice seventeenth-century tract towards censorship, Areopagitica:

The hazard of such unbounded liberty, and the hazard of bounding it, have produced an issue within the science of Authorities, which human understanding appears hitherto unable to unravel. If nothing could also be revealed however what civil authority shall have beforehand accredited, energy should at all times be the usual of reality; if each dreamer of improvements might propagate his initiatives, there could be no settlement; if each murmurer at authorities might diffuse discontent, there could be no peace; and if each sceptic in theology might educate his follies, there could be no faith. The treatment towards these evils is to punish the authors; for it’s but allowed that each society might punish, although not forestall, the publication of opinions, which that society shall suppose pernicious; however this punishment, although it might crush the writer, promotes the e book; and it appears no more cheap to depart the correct of printing unrestrained, as a result of writers could also be afterwards censured, than it could be to sleep with doorways unbolted, as a result of by our legal guidelines we will hold a thief.

Johnson is evident on this passage—as he was elsewhere in his work—that, if we’re a society that seeks reality, we can’t have pre-publication state censorship, for censorship collapses reality into energy. However, on the similar time, the absence of licensing causes harms of its personal—harms to settled authority, harms to public order, and harms to spiritual authority, too. Therefore the necessity to retain causes of authorized motion that may be taken towards authors whose work is seditious. And but, as Johnson surmises, this doesn’t at all times work. For one factor, going after a e book that’s seditious might serve solely to amplify that e book’s skill to broadcast its message and, for an additional, it’s no extra logical than encouraging a burglar to steal your possessions figuring out that you would be able to take authorized motion towards him after he has completed so. For Johnson, these seem like issues of fine governance that admit of no resolution. If we would like free speech, we are going to simply should put up with its vices, its drawbacks, and its inconveniences, faux information and disinformation included.

That’s not a brand new conclusion, even because the applied sciences of communication evolve. Quite the opposite, clear-sighted thinkers have understood it ever because it was first set out by Jonathan Swift.